L’IMMAGINE DI CARLO I STUART, RE E MARTIRE, SARA’ ESPOSTA NELLA CHIESA CAPITOLARE DELL’ORDINE DI SAN LAZZARO DI GERUSALEMME A MONREALE

L’IMMAGINE DI CARLO I STUART, RE E MARTIRE, SARA’ ESPOSTA NELLA CHIESA CAPITOLARE DELL’ORDINE DI SAN LAZZARO DI GERUSALEMME A MONREALE

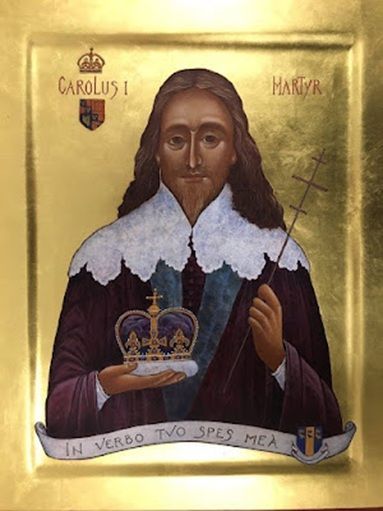

Un dipinto con l’immagine di Carlo I Stuart, Re d’Inghilterra, Scozia ed Irlanda, venerato come santo martire dalla Chiesa anglicana, sarà esposto nella chiesa capitolare dell’Ordine di San Lazzaro a Monreale, quale testimonianza della reale fratellanza fra la comunità cattolica ed anglicana di Sicilia e segno visibile del carisma ecumenico dell’Ordine.

Il dipinto, della metà del ‘600 ed attribuito ad Antony Van Dyck, sarà benedetto dal Vescovo anglicano David Hamid, durante il rito della sua ammissione nell’Ordine di San Lazzaro il prossimo 26 gennaio 2025.

Re Carlo il Martire, o Carlo, Re e Martire, è un titolo di Carlo I, che fu re d'Inghilterra, Scozia e Irlanda dal 1625 fino alla sua esecuzione il 30 gennaio 1649. Il titolo è usato dagli anglicani che considerano l'esecuzione di Carlo come un martirio. La sua festa nel calendario anglicano dei santi è il 30 gennaio, anniversario della sua esecuzione nel 1649.

Il culto di Carlo martire era storicamente popolare tra i conservatori. L'osservanza è stata una delle numerose “funzioni di stato” rimosse nel 1859 dal Book of Common Prayer della Chiesa d'Inghilterra e della Chiesa d'Irlanda. Rimangono alcune chiese e parrocchie dedicate a Carlo Martire e il suo culto è mantenuto da alcune società anglo-cattoliche, tra cui la Society of King Charles the Martyr fondata nel 1894 e la Royal Martyr Church Union fondata nel 1906.

Carlo I credeva in una versione sacramentale della Chiesa d'Inghilterra, chiamata Alto Anglicanesimo, con una teologia basata sull'arminianesimo, convinzione condivisa dal suo principale consigliere politico, l'arcivescovo William Laud. Laud fu nominato da Carlo arcivescovo di Canterbury nel 1633 e avviò una serie di riforme nella Chiesa per renderla più cerimoniale. Questo era attivamente ostile alle tendenze riformiste di molti dei suoi sudditi inglesi e scozzesi. Rifiutò il calvinismo dei presbiteriani, insistette su una forma episcopale (gerarchica) di governo della Chiesa in contrapposizione alle forme presbiteriali o congregazionali e richiese che la liturgia della Chiesa d'Inghilterra fosse celebrata con tutte le cerimonie e i paramenti richiesti dal Book of Common Prayer del 1604. Il Parlamento d'Inghilterra si oppose sia alle politiche religiose di Carlo sia al suo governo personale dal 1629 al 1640, durante il quale non convocò mai il Parlamento. Queste dispute contribuirono alla guerra civile inglese.

Dopo che i realisti furono sconfitti dai parlamentari, Carlo fu processato. Fu accusato di aver tentato di governare come monarca assoluto piuttosto che in collaborazione con il Parlamento; di aver combattuto contro il suo popolo; di aver continuato la guerra dopo la sconfitta delle sue forze (la Seconda guerra civile inglese); di aver cospirato dopo la sconfitta per promuovere un'altra continuazione; e di aver incoraggiato le sue truppe a uccidere i prigionieri di guerra. Fu condannato a morte.

Era pratica comune che la testa di un traditore venisse sollevata ed esibita alla folla con la scritta “Ecco la testa di un traditore!”. Anche se la testa di Carlo fu esposta, le parole non furono usate. Con un gesto senza precedenti, uno dei leader di spicco dei rivoluzionari, Oliver Cromwell, permise di ricucire la testa del re sul suo corpo in modo che la famiglia potesse rendergli omaggio. Carlo fu sepolto privatamente e di notte il 7 febbraio 1649, nella volta di Enrico VIII all'interno della Cappella di San Giorgio nel Castello di Windsor.

Carlo è considerato dalla Chiesa d'Inghilterra un martire perché, secondo alcune fonti, gli fu offerta la vita se avesse abbandonato l'episcopato storico della Chiesa d'Inghilterra e che abbia rifiutato ritenendo che la Chiesa d'Inghilterra fosse veramente “cattolica” e dovesse mantenere l'episcopato cattolico. La sua designazione nel calendario della Chiesa d'Inghilterra è “Carlo, Re e Martire, 1649”.

Dopo la restaurazione della monarchia del 1660 le Convocazioni della Chiesa d'Inghilterra di Canterbury e di York aggiunsero la data del martirio di Carlo al proprio calendario liturgico.

La commemorazione di Re Carlo I è inserita nel calendario dell'Alternative Service Book del 1980 ed in una nuova colletta composta per il Common Worship nel 2000.

Ci sono alcune chiese e cappelle anglicane dedicate a Carlo Re e Martire in Inghilterra, Scozia, Irlanda, Stati Uniti, Australia e Sudafrica.

Il culto di Carlo I Re e martire è sostenuto dalla Society of King Charles the Martyr, anche con una cappella cattolica presso l’Ordinariato Personale della Cattedra di San Pietro, per gli anglicani degli Stati Uniti entrati in piena comunione con la Chiesa Cattolica Romana, cappella istituita con l’approvazione del vescovo Steven J. Lopes.

THE IMAGE OF CHARLES I STUART, KING AND MARTYR, WILL BE DISPLAYED IN THE CAPITULAR CHURCH OF THE ORDER OF SAINT LAZARUS OF JERUSALEM IN MONREALE

A painting with the image of Charles I Stuart, King of England, Scotland and Ireland, venerated as a martyr saint by the Anglican Church, will be exhibited in the capitular church of the Order of San Lazzaro in Monreale, as a testimony of the real brotherhood between the Catholic and Anglican communities of Sicily and a visible sign of the Order's ecumenical charisma.

The painting, dating from the mid 17th century and attributed to Antony Van Dyck, will be blessed by the Anglican Bishop David Hamid during the rite of his admission into the Order of St. Lazarus on 26 January 2025.

King Charles the Martyr, or Charles, King and Martyr, is a title of Charles I, who was King of England, Scotland and Ireland from 1625 until his execution on 30 January 1649. The title is used by Anglicans who regard Charles' execution as a martyrdom. His feast day in the Anglican calendar of saints is 30 January, the anniversary of his execution in 1649.

The cult of Charles the martyr was historically popular among conservatives. The observance was one of several ‘state services’ removed in 1859 from the Book of Common Prayer of the Church of England and the Church of Ireland. A few churches and parishes dedicated to Charles the Martyr remain and his cult is maintained by a number of Anglo-Catholic societies, including the Society of King Charles the Martyr founded in 1894 and the Royal Martyr Church Union founded in 1906.

Charles I believed in a sacramental version of the Church of England, called High Anglicanism, with a theology based on Arminianism, a belief shared by his chief political advisor, Archbishop William Laud. Laud was appointed Archbishop of Canterbury by Charles in 1633 and initiated a series of reforms in the Church to make it more ceremonial. He was actively hostile to the reformist tendencies of many of his English and Scottish subjects. He rejected the Calvinism of the Presbyterians, insisted on an episcopal (hierarchical) form of Church government as opposed to presbyterial or congregational forms, and demanded that the liturgy of the Church of England be celebrated with all the ceremonies and vestments required by the 1604 Book of Common Prayer. The Parliament of England opposed both Charles' religious policies and his personal rule from 1629 to 1640, during which time he never convened Parliament. These disputes contributed to the English Civil War.

After the Royalists were defeated by the Parliamentarians, Charles was put on trial. He was accused of attempting to rule as an absolute monarch rather than in collaboration with Parliament; of fighting against his own people; of continuing the war after the defeat of his forces (the Second English Civil War); of conspiring after defeat to promote another continuation; and of encouraging his troops to kill prisoners of war. He was sentenced to death.

It was common practice for a traitor's head to be lifted up and displayed to the crowd with the words ‘Here is the head of a traitor!’. Although Charles' head was displayed, the words were not used. In an unprecedented gesture, one of the prominent leaders of the revolutionaries, Oliver Cromwell, allowed the king's head to be sewn onto his body so that the family could pay their respects. Charles was buried privately and at night on 7 February 1649, in Henry VIII's vault inside St George's Chapel in Windsor Castle.

Charles is considered by the Church of England to be a martyr because, according to some sources, he was offered his life if he abandoned the historic episcopacy of the Church of England and refused, believing that the Church of England was truly ‘Catholic’ and should retain the Catholic episcopate. His designation in the Church of England calendar is ‘Charles, King and Martyr, 1649’.

After the restoration of the monarchy in 1660, the Church of England Convocations of Canterbury and York added the date of Charles' martyrdom to their liturgical calendar.

The commemoration of King Charles I is included in the Alternative Service Book calendar of 1980 and in a new collection composed for Common Worship in 2000.

There are a number of Anglican churches and chapels dedicated to Charles King and Martyr in England, Scotland, Ireland, the United States, Australia and South Africa.

The cult of King Charles the Martyr is supported by the Society of King Charles the Martyr, also with a Catholic chapel at the Personal Ordinariate of the Chair of St. Peter, for Anglicans in the United States who have entered into full communion with the Roman Catholic Church, a chapel established with the approval of Bishop Steven J. Lopes.